Welcome to our guide to financial instruments.

Here we will discuss what are all the "things" that you can buy or sell in regulated or unregulated markets, explore how they work and when/how to use them.

The concept is core to what we want to do: in fact investing is about trading one or more financial instruments with the aim to grow our initial capital, to ultimately achieve financial freedom.

Here's the map to our journey:

Financial instruments

Financial instruments are just assets that can be traded between counterparties. They represent a legal agreement typically used to transfer rights against money.

They come in different types and forms, and here we will divide them by asset classes:

More insights on types here (cash vs derivatives).

Where to trade assets in general? We just need to know for the moment that financial instruments can be traded in centralized exchanges, or via ad hoc transactions (over-the-counter), with a different degree of complexity for the final investor.

Ok, cool. Let's know explore asset classes in detail.

Equities

Stocks, also called equities, are instruments (= securities) representing the ownership of a fraction of the issuing company, listed on an exchange. You might have heard also the term shares, which are simply units of stocks: here we will use stocks, shares or equities indifferently.

Why do stocks exist?

On one side stocks allow companies to raise funds to operate their businesses, and on the other side they allow investors to own a proportion of both the company's assets and profits, which can increase (or decrease) in value over time.

Where to buy them?

After a company goes public through an initial public offering (IPO), its stocks becomes available on a regulated exchange (think NASDAQ in the US, or London stock exchange in Europe for example). The individual investor can buy equities using a broker account or platform depending on their location.

Why should we own stocks?

Stocks provide two potential benefits to the final investor: capital appreciation and income via dividends.

Which are the risks involved?

Remember that investing is a risky business, I mean we are all paid to take risk: stock prices can go up and down, therefore there is no guarantee - as in almost all investments - to preserve your initial capital.

It is also true though that equities have been historically able to outperform many other financial assets. If stocks can show various degrees of price volatility and can wipe out the initial invested capital in case of bankruptcy of the issuing company, under specific conditions (see rising inflation) certain types of stocks - such as value stocks for example -can outperform other assets typically considered safer.

How to invest in stocks?

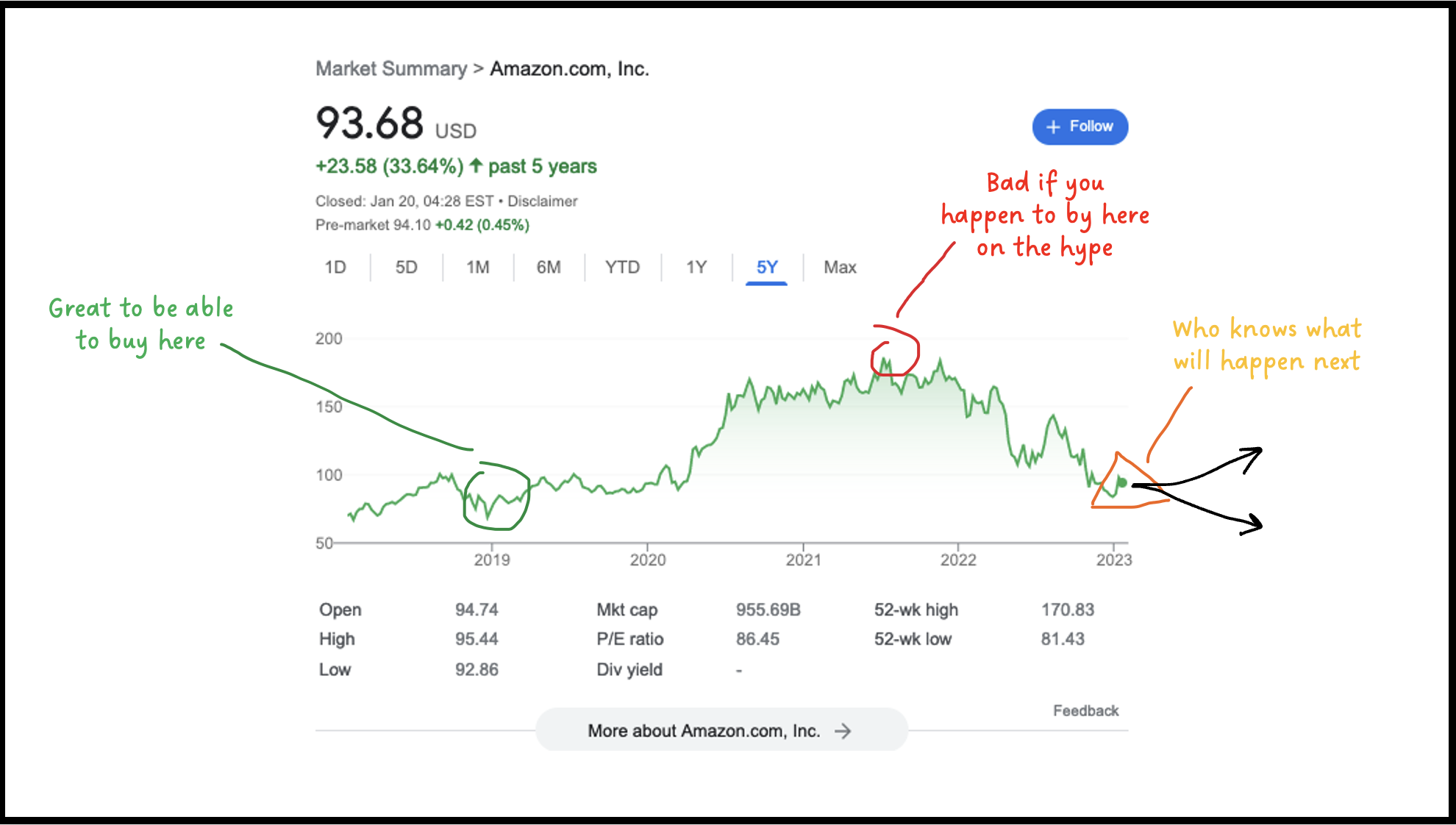

You can buy individual stocks (think Amazon, Coca Cola) and own them over long periods of time. This is an easy and valid strategy, with the caveat that the company that you select should not go bankrupt or perform poorly over the selected time-frame, and that you buy it at the right price (not at peak). That's not easy to do, despite a plethora of websites teaching how to beat the market by cherry picking stocks.

See below what I mean by buying at the right price...I mean, who knows?

You should know that here at Monetharia some of us come from broad experiences on the trading floors of the biggest investment companies in the world, and we have been working with fund managers to study and assess when exactly to buy individual stocks. The short summary is that it is really hard to do even for professionals.

We think that a better idea is to:

Can we anticipate the direction of stock prices, up or down?

We just said above that it is very hard to predict what individual stocks will do. But we can do something: it is much easier to predict what similar stocks, all together, can do.

In fact you should know that individual stocks move for stock-specific information very rarely: it happens when there are major (positive or negative) news on a specific company, or when company earnings are published), just a few days per year.

For the rest of the time, stocks tend to move on macro-specific trends: economic growth, inflation, monetary policy and geopolitical events.

Interest rates go up? Growth and technology stocks will suffer. Inflation goes up suddenly? High dividend stocks will outperform. Is economic growth recovering after a depression? Cyclical stocks and small caps usually win.

This is to say that specific groups of stocks tend to show similar behaviors under macro-specific events, and we can read those events and historical correlations to our advantage.

We are working on a specific article to share how to "use" factor investing or sector investing in the equity space to your advantage.

We are also building an investment vehicle that, driven by macro and momentum investing, will be able to use to its advantage predictable and mechanical stock trends. We will keep you posted.

More insights on stocks here.

Bonds

A bond is a financial instrument representing a loan taken by a government or a company from investors.

Why do bonds exist?

Imagine that the German government needs money for whatever reason. It can go to a bank (or a pool of banks) asking for a loan, or - an an alternative - can go to the open fixed income market and ask for money under the form of a bond contract. The concept is the same.

In practical terms, this is how a bond works: the bond issuer - Germany in our example - receives money (capital) and pays a periodical interest coupon, as a percentage of the bond initial (face) value. Germany would then return the initial capital (principal) on the maturity date, ending the loan.

Investors can lend money buying a bond and hold it until the end, or can exchange the bond - similarly to stocks - in the open market (called secondary market in this case). Consider that the end investor will receive a yield from the bond agreement, where yield means the annual return on capital from the investment if the bond is held until the end of the contract (maturity), but can also benefit from capital appreciation if a bond price goes up.

Without going too technical, you should know that when a bond yield goes up, a bond price goes down and viceversa.

Where to buy them?

Bonds are not exchanged in centralized markets, but they are traded over the counter. It is hard for the individual investor to buy single bonds, but it is instead easy to buy fixed income mutual funds or ETFs via an investment account wherever you are based.

Why should we own bonds?

Bonds tend to behave very differently from stocks and so they act as powerful diversified in a portfolio. Let's say as simple example that we are entering into an economic recession: stocks markets would fall, while bonds issued by cash-rich governments, say USA or Germany, would rally, providing great benefits to an individual portfolio.

More on this further below.

Which are the risks involved?

Bonds are considered safer assets than stocks, but this is a gross error in some cases. We need to look into this in greater detail.

There are two key risks in bonds:

1. Interest rate risk

A bond yield is sensitive to changes in interest rates by central banks, and also market expectations on future interest rates. This means that bond yields can move up or down every day, and subsequently prices can move daily too.

Well, if interest rates go up, or are expected to go up at some point, bond yields will move higher and prices will move lower. Ouch. Similarly, the opposite is true when rates move lower, or when they are expected to move down in the future: yields down, price up.

This is why safe government bonds from rich countries, such as Switzerland, Germany or USA, piled up massive losses in 2022 when aggressive inflation was pushing central banks to hike interest rates. But this is also why some government bonds can do very well when economic growth slows down: markets would expect interest rates to go down at some point, pushing yields down now and prices up.

We measure interest rate risk with duration, which measures how long does it take for a bond (interest coupons and principal) to repay the investor of its initial investment, or loan to the bond issuer.

2. Credit risk

The bond issuer - say Germany, Argentina, Apple or Netflix - can have a sound business, or not. Depending on how its business goes over time, such bond issuer might have the money, or not, to pay back the principal at the end of the contract. That's a risk that the investor needs to take.

Specific entities, called rating agencies, can help by adding a rating (a measure of creditworthiness) to each bond issuer, and even to each single bond depending on the clauses in the contract.

The sum of interest rate and credit risks can help the investor understand when is the time to own bonds (and which ones) or not.

Find many more insights here and here.

How to invest in bonds?

We can either own bonds until maturity and cash in the interest payments received from the bond issuer, or trade bonds in the market.

The former option is easier and would remove interest rate risk from the equation, but would increase the exposure to any given credit risk for the lifetime of the bond contract. Such way of investing would also remove the possibility of gaining any bond price appreciation.

The latter option is more typical for professional investors, with bonds traded frequently as it happens with stocks.

With active trading, we need to pay attention to a couple of things:

The suggestion is again to delegate the day to day trading and management of bonds to ETFs or to fixed income funds, and focus only on what duration you want and what credit risk you want in your portfolio: several different funds will satisfy your needs.

We will publish soon an article discussing in detail when to use which bonds in which part of the economic cycle. In our investment vehicle, the bond component is absolutely key to ride different parts of the cycle.

Commodities

Commodities are basic raw materials, or goods, that can be exchanged. We can split the main types of commodities in three families: agricultural products (meet, cereals, orange juice, coffee, sugar, etc.), metals (copper, gold, aluminum, etc.) and energy products (oil, gas, etc.).

As an asset class, commodities are sensitive to supply and demand, as any other asset, but are also very sensitive to changes in economic conditions.

For example, do we expect global economic growth to increase next year? Assuming no changes in supply, the oil price should then go up. Is China slowing down for whatever the reason? Expect copper price to go down.

Commodities can act as powerful diversifiers in our investment portfolios, but they are incredibly hard to trade in their own physical markets - participated by professional traders and companies - but can be approachable by individual investors via mutual funds or ETFs.

Currencies

Fiat currencies are another type of instrument that we can trade.

We can buy and sell a currency pair (think USD vs EUR for example) with the aim to generate a profit from currency movements.

In fact, currencies tend to move in specific ways under specific macroeconomic conditions and can allow us to use them as effective, additional assets in our portfolios.

Did you know for example that when the Fed, i.e. the US central bank, hikes interest rates earlier or faster than other geographies, the USD tends to appreciate? This also happens when a global recession is coming up, for example.

Find more insights here.

Cryptocurrencies

Cryptocurrencies, such as the Bitcoin or Ethereum, are digital assets with some specific characteristics:

Transactions in cryptos employ a “trust-less” system of verification: this means that users don’t have to rely on a third party for verification. The system itself is self-governing by leveraging blockchains, which are distributed databases updated by the nodes, or participants, on a certain form of consensus.

If you are willing to know more about the origins and functionalities of cryptos, the very best article we have ever found on the topic is this one here.

Do cryptos have any value?

Some do, some don't.

Our take is that we need to consider each currency like a company: is this company making money with a business model? Then, its cash flows provide a sort of value to the investor. For example, you can check the annualized revenues made by the Ethereum here (approx. USD 1 billion at the time of writing).

Cryptos that do not generate revenues and/or have no reasonable utility, and/or are illiquid may often be a trap.

How risky is to invest in cryptos?

Given the lack of predictability of emerging technologies, lack of visibility on revenue streams, counterparty risk (think about the collapse of FTX among others) and the lack of measurable intrinsic value, investing in cryptocurrencies is very risky.

How to invest in cryptos?

Several open projects provide a lot of useful metrics to understand where prices of key coins and tokens might go in the near future, such as Token Terminal, Messari, Glassnode and others, by leveraging technical indicators or on-chain analysis. But there is no certainty, as usual with most asset classes, on where prices might go in the future.

At Monetharia, we like cryptos. We consider them a high-beta asset, or an asset that moves in the same direction of key stock and bond markets but with greater amplitude, responding well (since 2018) to macro trends and that can provide a source of diversification in the short term.

Mutual funds and ETFs

We finish this guide by mentioning other financial instruments that are very important for the end investor, like you, such as funds.

Funds are baskets containing different investments at the same time. This means that in one transaction the final investor will own many different things at once.

Funds often bundle together assets with something in common, such as a specific asset class (say equities), or a specific sector (say financial stocks), or a specific geography (say emerging market bonds).

Mutual funds are professionally managed by reputable companies (the majority of the times) and by investment professionals with several resources (technology, research and analyst pools, market access) behind their backs, and so they tend to be a preferred way to invest vs buying individual assets alone.

While it is not always the case, mutual funds typically aim to beat their market of reference by taking active investment positions.

Buying and selling mutual funds usually takes long time: it is in fact typical for a purchase to take 2 or more days to be accounted for, and the same is for selling a position. This means that it is close to impossible to trade mutual funds on individual news or for the short term.

ETFs, or exchange traded funds, are also baskets of different assets, with the peculiarity that they tend to passively copy specific markets or indices.

This means that they replicate, for good or bad, the performance of individual markets without trying to beat them. They have two major advantages: they trade like an individual stock, with immediate recognition of each transaction, and they tend to be much cheaper (in fees) than active mutual funds.

We will dedicate an entire article to this topic.

Well done to you to get to this point. We hope the guide can help you find your way into investing in financial markets.

- - - - - -

Suggested books on the fundamentals of investing

via Amazon.es

Educacion financiera avanzada partiendo de cero

via Amazon.com

The little book of common sense investing

All pictures are sourced via pexels, vecteezy, unsplash or freepik